Design and Management of The Transition State of Strategic Change

This blog article attempts to describe the complex transition phase of the old and weak 3-state strategic change model in terms of two elements of the new and strong strategic management model: strategy formulation and implementation: which incorporates the portfolio management framework to facilitate and provide clarity to the implementation process.

Basically, organizations undergo two types of strategic change: the first type of change is a continuous change in which organizations continuously change to keep pace with their changing environment or when an organization anticipates a need for a pre-emptive change to meet external challenges, and the second type of strategic change is a reactive change that occurs in response to organization’s declining performance. This performance can decline rapidly in the short term or gradually over many years to justify the need for strategic change. The first type of change is an incremental or evolutionary change that generates some response to the competitive challenges the organization faces, but not enough to keep the organization in step or pace with the rapidly changing external business environment.

Therefore, to meet the external challenges of the twenty-first century, every organization should embrace change on an ongoing basis. Change can occur in many different forms and need not to be only in a revolutionary manner. In fact, the end results of change can be placed on a continuum: at one extreme is the less-fundamental change implemented slowly or gradually, and on the other extreme is the complete revolutionary change. Each organization is unique in its position, so there can be various types of changes in between the continuum. Moreover, based on the key success factors alone, a company can exploit unique strategies to change in order to improve profitability. And for these reasons, there is no standard recipe to manage change. The content of change (what should be changed) needs to be determined by the internal and external organizational context. Strategic change should only be undertaken after evaluating all possible alternative ways that can restore the organization to its competitive position.

Current State

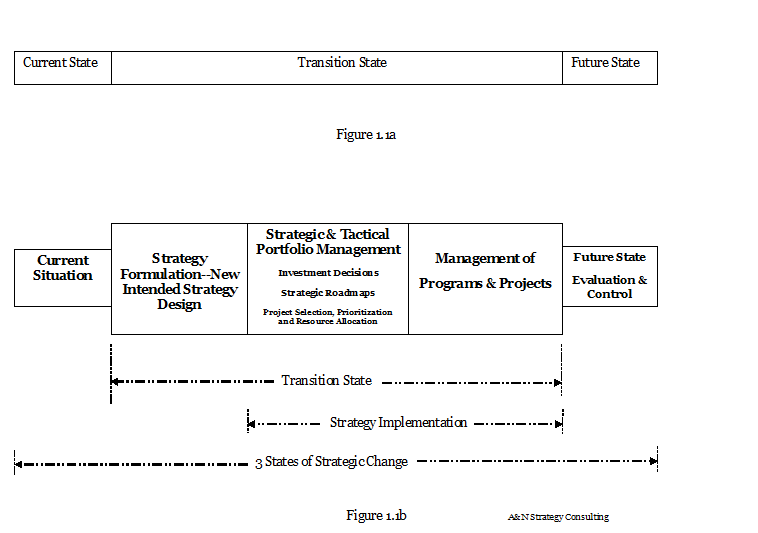

The basic model to manage strategic change comprises three stages or phases: the current, the future, and the transition (see fig 1.1a). A thorough strategic analysis is imperative in practice to understand the organization’s current situation to determine why change is needed and what it should change to, to reach the desired goals. However, many change agents fail to understand the organization’s current situation correctly, and therefore, can ignore the required change needed or rush to select a standard existing solution that might not be appropriate for the organization’s current change context. Implementing the wrong solution could lead to strategic disaster. The following two examples provide some insights. Sometimes in a pre-emptive attempt to follow the leader: imitating a competitor’s business strategy could be considered very harmful. In the 1960s, Fujitsu, a computer manufacturer which competed in the mainframe computer market, had a goal to catch up with IBM but failed to recognize that the mainframe business was reaching its maturity, due to the disruptive effect caused by the advent of microcomputers. In another example, one company’s (unknown name in reference) particular business unit reported steady growth in profits with high levels of return on invested capital (ROIC) for a few years. The headquarter executives questioned little about what is driving these profits. The market share was declining–that went unnoticed for some time. Later, it was found that the business unit was driving profits by raising prices and at the same time reducing marketing and advertising costs. Higher prices and reduced marketing expenditures allowed competitors to snatch market share away from this business unit. It took many years for this company to recover its lost market position.

Transition State

The transition state of strategic change can be shaped and defined in terms of the two basic elements of the strategic management model: strategy formulation and implementation, as shown in figure 1.1b.

New Intended Strategy Formulation

After the why and what of change is analyzed, the change agents should determine the change approach, which includes the end results of change and nature of change, and the change path that will be required to bring back the organization to its competitive position. Nature of change is the manner by which the change will be implemented: either rapidly or slowly through stages or phases. When considering change, the new strategy formulation process should be assessed to determine the change path: the sequences of changes needed to deliver the change. For example, in 2004, Fiat first initiated reconstruction efforts and after that an evolution to achieve transformation of the company. The firm’s internal and external environment should be analyzed to gain an understanding of why change is necessary to the current state. Sometimes a poor analysis and judgment of the current situation could mislead the entire change efforts that could further deteriorate the firm’s competitive position instead of improving it.

Before implementing a strategic change, the implementation plan should be evaluated and addressed initially when the pros and cons of strategic alternatives are analyzed. After formulating the new change strategy and selecting the change path, the new strategy and goals are translated into strategic initiatives that will guide the real implementation of change. Strategic change initiatives are costly and time-consuming, and there is no guarantee that these initiatives will deliver successful results. Research indicates that only about 50% of the change initiatives produce successful results and, on top of that, they bear the risk of sustainability. The reasons behind the failed initiatives can be enormous. Delta Airlines’ “Leadership 7.5” restructuring program (see example below) initiated in 1994 went awry. The poorly managed program, which was wrongly focused on cost-cutting, only caused the company to lose its reputation for stellar service. Employee morale suffered and the corporate culture was dented.

Strategy Implementation

The transition state is the process of changing the organization from its current state to the desired future state. The difference between the future and the current state is the performance gap. Strategy implementation can further be partitioned into two subphases: (1) translation or the design of transition in which the intended new strategy is put into action by designing portfolios of programs and projects, and (2) actual implementation in which strategy is implemented through programs and projects to deliver the future State’s desired outcome.

Translation Phase

The new intended strategy is translated into the two components of portfolio management: strategic and tactical portfolio management. Strategic portfolio management deals with decisions related to the cost and time dimensions of strategy: investment decisions (cost-related) and strategic roadmaps (initiatives and timelines) decisions. Tactical portfolio management decisions follow the strategic decisions and are related to individual portfolios of programs and projects. These decisions involve project selection (go/no go), prioritization, and resource allocation to projects. The process of strategic and tactical portfolio management is well structured and hierarchical, which allows translating the strategy into portfolios of programs and projects ready to be implemented. Therefore, portfolio management, when used to implement strategies, can help to achieve three major goals and objectives: maximization of value, portfolio balance, and strategic alignment.

Management of Programs and Projects

Organizational change involves doing some sort of work. The best modern way to perform any work is through programs and projects. Projects are temporary endeavors, unique, and initiated to create deliverables. A program is a group of related projects. Programs are initiated to realize change and competitive advantage for the organization. The best way to achieve organizational goals and objectives is to link projects to the organizational strategy through programs and portfolios. In this phase programs and projects are implemented to reach the desired goals and objectives of the intended new strategy. Change management programs and projects are typically undertaken to achieve culture change, improve efficiency, provide training, develop capabilities, and achieve transformation and innovation.

Future State

The future state delivers the end results of strategy implementation. Performance is assessed based on the change management goals and objectives that were set during the new intended strategy formulation process. Since the goals and objectives of change are typically related to profitability, the organization should set performance measures when the strategy is formulated that predict and influence future profitability, such as steering controls. Each industry has its own set of performance measures that can predict future profits. Airlines monitor cost per available seat mile (CASM). For example, to regain its lost competitive position and return to profitability, Delta Airlines initiated a turnaround strategy “Leadership 7.5” in 1994, which was evaluated in terms of the cost of a seat per mile of flight of each airplane. Before the program was initiated, the cost per seat was 9.76 ¢. The objective was to reach 7.5 ¢ by the end of June 1997. By the end of 1995, the cost came down to 8.4 ¢, and unfortunately, the program was not evaluated after that as it was abandoned by July 1995.

Finally, corrective action should be taken when performance is not in line with the desired goals and objectives in the area of intended strategy formulation and implementation. This evaluation and control phase completes the strategic change management model.

References and Further Reading

- R. Beckhard and R. Harris, Organizational Transitions: Managing Complex Changes, 2nd edn (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987).

- J. Balogun, V. Hope Hailey and S. Gustafsson, Exploring Strategic Change (United Kingdom: Pearson Education Ltd., 2016), Chapters 1 and 2.

- E. Romanelli and M. Tushman, Organizational Transformation as Punctuated Equilibrium: An Empirical Test, Academy of Management Journal(October 1994), 37(5), pp. 1141-66.

- R. M. Grant, Contemporary Strategy Analysis (United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2013), Chapters 3 and 8.

- T. L. Wheelen & J. D. Hunger, Strategic Management & Business Policy (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2000), Chapters 1 and 10.

- Tim Koller, Richard Dobbs, and Bill Huyett, The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011), p. 226.

- Robert G. Cooper and Scott J. Edgett, Product Innovation and Technology Strategy (U. S.: Product Development Institute Inc., 2009), Chapters 6 & 7.

- Robert G. Cooper and Scott J. Edgett and E. J. Kleinschmidt, Portfolio Management for New Products (N. Y.: Basic Books, 2002), Chapter 5.

- T. L. Wheelen, J. D. Hunger, Alan N. Hoffman, and Charles E. Bamford, Strategic Management & Business Policy (United Kingdom: Pearson Education Ltd., 2018), Chapter 12 .

- Adam Bryant, Focus on Costs May Have Blurred Delta’s Vision – The New York Times.

Comments

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!